Dutch Realist Genre Painters

Pieter Claesz (c.1597 to 1660)

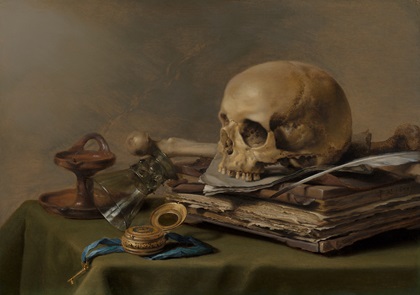

Pieter Claesz’s was a Dutch artist who specialised in creating breakfast table pieces and vanitas works and which can generally be categorised into three separate eras. In the first, Claesz created works which tended to have many objects on view, including such things as fruit, vases and spices, but also such items as a skull to include the messages of morality. Usually, their palettes rather muted and held rather subtle tonal transitions. In his second era, his works were rather decluttered, with only one glass and piece of food, for example, but with a warmer but still muted palette. Claesz would also include table corners to assist in creating a sense of depth within his pieces. In the third stage of his development as an artist, Claesz’s pieces evolved to include more colour and emotion, and the amount of objects included rose drastically once again, but excluding the allegorical messages. Instead, Claesz included more lavish and exotic items.

Fig. 1. Claesz, P. Vanitas Still Life (1630)

Fig. 2. Claesz, P A Silver Beaker, a Roemer and a Peeled Lemon (1636)

Fig. 3. Claesz, P Still Life (1652)

From looking at Claez’s works, I think the middle stage of his artistic development is definitely my favourite as I really like the minimal amount of objects within. The first is rather interesting and the skull draws me into the piece, however, the other objects do not hold as much interest for me. As with the third, I find there are too many things to try and consider all at once and so am not as drawn to them. I think I should bear this in mind in my own work also.

Frans Hals (c.1582 to 1666)

Franz Hals specialised in portraiture of both individuals and groups, and is known for portraying spontaneity, personality and character within his informal pieces, which was quite unheard of at the time and could potentially be considered as a very early photograph, but without the camera. Whilst Hals is known for using muted palettes, he was able to create a vibrancy in his pieces, however, this tailed off towards the end of his life with his pieces appearing murkier and duller in this stage.

For his group commissions, Hals was paid in equal parts by all portrayed, so each wanted equal prominence and character within the piece. As a result, there is rather little in the way of fading into the background of the figures as though simply extras and they almost appear to be lit as a photographer would light their models.

Whilst Hals’ earlier works are more carefree and expressive, almost as though they were a teenager, his later works were more formal and mature with a much calmer aura to them. This leads the viewer to grow with Hals as though reading a private diary.

Although he would usually work freely and spontaneously onto the canvas, he would also sometimes create under-drawings before beginning properly.

Fig. 4. Hals, F. Buffoon Playing a Lute (c. 1623 to 1624)

Fig. 5. Hals, F. Meeting of the officers of the Kloveniersschutterij in Haarlem (c. 1633)

Fig. 6. Hals, F. Portrait of René Descartes (cleaned up) (c. 1649)

Looking at Hals’ works, I am instantly drawn to Fig. 4. and the happy-go-lucky approach adopted. I can almost see the ‘buffoon’ dancing around in a care-free manner. The vibrancy in the face is just beautiful and it is strange that I am drawn to the eyes when, really, all there is to be seen to them is the whites. It is peculiar to me that the instrument appears flat next to the depth of the man. I think this is an indication of Hals’ naivity at the time. By comparison, the dark, broodiness of Fig. 6. speaks of Hals’ inevitable maturity. The sitter is not only older than the ‘buffoon’, but is portrayed with different brushstrokes, use of palette and formality. I am more drawn to the methods displayed in his earlier works, but I will definitely bear in mind Hals’ works in the future – especially his penchant for having a wide variety of blacks!

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn(1606 to 1669)

Rembrandt is by far considered to be the most important Dutch artist of all time for his phenomenal workmanship and sincere humility within his works. Whilst it was quite common for artists to specialise in a small number of genres, Rembrandt’s skill was extended over a vast array, including historical, mythological and biblical narratives. his work is instantly recognisable by its deep, muted palettes, indicating a low lighting level, but also by the auras surrounding the sitter’s head. Rembrandt is also infamous for the invisible line he would draw down the centre of the sitter’s face, with the nose being the main note of the divide and portraying one half of the face with luminosity and the other in deep shadows.

With regard to the humility Rembrandt would show in his self-portraits, he would also dress up in clothes from earlier times and would even pull faces at himself, adding a touch of comedy to his pieces. All of this was rather unique for Rembrandt’s time and, as a result, he became very popular for portrait pieces, however, it was known that his ability to create a likeness was not always on par. Rembrandt would often depict himself within his pieces as a member of the crowd – not the main character, merely a spectator to the unfolding events. This fascinates me as it is really exciting to try to find him within the pieces and to question who his character is within that world.

The attention Rembrandt gave to the details within his pieces and the emotion within led him to be commissioned to create what is considered by many to be his ultimate masterpiece, as can be seen in Fig. 8, which he used to get a hold of technical and compositional difficulties he had endured previously. After this work was finalised, Rembrandt began to slide more towards the methods being used at the time and his works began to mature. As a young man, Rembrandt created works which were almost flawless in their depiction; the brushstrokes were very smooth and delicate. In his later works, in which he shows himself to have aged and the flaws which come with the same, the brushstrokes are rather loose and unforgiving. He also loses the invisible line dividing the face into brightness and gloom.

Fig. 7. Rembrandt. Self-Portrait with Gorget (c. 1629)

Fig. 8. Rembrandt. The Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburgh, known as the ‘Night Watch’ (1642)

Fig. 9. Rembrandt. Self-Portrait (1669)

When I came to looking up some of Rembrandt’s works, I was instantly drawn to Fig. 7. as the face shown within is unbelievably beautiful. The emotion portrayed by just some well-placed paint is utterly phenomenal. The Rembrandt within this piece appears so gentile and naive with a real sense of fragility. Fig. 9. also shows this gentle nature, however, there appears to be more of a sadness to this piece and the humility much more prominent. With portraiture fast becoming my favourite genre, the colours and emotion found within these works is by far the strongest lesson I feel I want to take from this research point.

Interiors, Illusions of Space and Rules of Composition

Having looked at interiors and the rules of composition in depth in my previous course, I decided to have a bit of a recap for this Research Point to refresh my memory of the two topics, but actually came across some other aspects I had not found previously, which included the following:

Interiors / Illusion of Space

Interiors came into being as their own genre during the 17th century in Europe. At first, these pieces were created to be almost a snapshot in time of people’s homes and focused solely on describing the contents of the home, almost as though as a portrait, still life or landscape painting would describe its contents. These pieces were generally created in watercolour and, whilst similar to other genres in that it required much in the way of skill and technical precision, this was a method which could be enjoyed by all and was prominent at a time when young, wealthy ladies were often bound to their rooms creating tapestries and other delicate creative pieces. The delicate nature of watercolours thus suited the ‘gentler sex’ very well and whilst the pieces these young women would create often lacked the technical skill required, they did include some characteristics which held charm and an insight into the ladies’ ways of life as well as more creativity than their professional counterparts.

The professional artists who undertook this type of creation generally did so as a way to bring new custom into architectural firms, to be able to give them a visual idea of the concepts were being put to them.

These pieces later became somewhat of a craze for the wealthier members of society who would commission pieces, for instance, to be able to show the lesser members of society how the other half lived without actually having to allow them to invade their personal space physically. Naturally, the middle classes would try to emulate the wealthy and would also commission these pieces of their own homes, mostly as a way of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ so to speak, but also to remember what their homes were like since fashions and trends were constantly shifting. Doing this would also allow them to share with their future generations how things were in times gone by.

Whilst there was no actual people in a lot of this type of art, the echo of people and the sense of home are often well documented within these pieces, with such things as empty glasses or open books giving the idea of someone having just left as we entered. In other pieces, as in Brownrigg’s piece above, people were shown depicting a narrative which the artist wanted to portray.

Johannes Vemeer

I decided to take a closer look at Johannes Vemeer who was a keen interior painter. Vemeer was very sophisticated and self-conscious in his work, and aimed for naturalism and strict empiricism, drawing on his own life experiences to create his pieces, as opposed to creating narratives or attempting to recreate historical, biblical or mythological stories within his pieces. Vemeer used his family members as models – and only as models, portraying none of the family’s emotion or turbulence – within his pieces, as well as sometimes ‘super-imposing’ himself into his pieces by such means as placing two mirrors at specific angles so as to project himself into a given space. He also tried to create a sense of calm and order within his pieces.

A large number of Vemeer’s works were created in his studio with the light coming from the left – the window sometimes unseen. Several pieces see Vemeer’s wife posing in the same positions and the clothing was almost always very similar in their appearance.

Many believe that Vemeer painted exactly what he saw as he saw it, others thought the rooms may have been completely imagined, whilst others believe he may have used a camera obscura, which was an earlier way of manipulating optical effects. The floors of his pieces often showed quite strongly contrasting patterns and geometric shapes which would assist in creating the illusion of depth (as well as the placement of windows, beams and other such objects).

Fig. 12. Vemeer, J. (1662 to 1664) The Music Lesson

Fig. 13. Vemeer, J. The Concert (c. 1664)

Fig. 14. Vemeer, J. (1670 to 1671) Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid

When looking at Vemeer’s works, I am immediately drawn to the contrasting flooring which just instantly draws me in. for me, the characters within the piece do not appear as interesting as the rest of the pieces – the paintings within the paintings are just phenomenal and the colours of the walls and windows portraying light in such a natural way is very interesting. Whilst not something I feel I would wish to recreate, I can fully appreciate their splendour and the intricacy with which they have been created. I do think I would like to take aspects of the patterned floor further though in experimentation.

Contemporary Interior Artists

Fig. 15. da Milano, G. Interior of the Painter’s Studio (1919)

Fig. 16.Aafjes, E Table Still Life (2018)

Fig. 17. Harris, K. Interior with Piano, Bantry House (2019)

Turning quickly to the works of contemporary artists within this method of working, I was immediately drawn to the above three pieces. I love the varied greys used within Fig. 15. and subtle changes in tone within it, but also the illusion of depth created as a result. The thin white line used to separate the canvas in the background and the wall in the foreground is very interesting to note. In Fig. 16., I really like how the artist has used really mild hues within the piece as well as a reversal of ground colourings. Where the foreground is usually richer and darker, and the background paler and lighter in colour, this piece has completely reversed it. I find this fascinating. Fig. 17. drew me in instantly due to the depth created by the windows, curtains and doorways. I would rather like to try and recreate something similar to this myself, so will bear this in mind for future interior pieces.

Rules of Composition

- The further away objects are, the more the colour in the object will lose its saturation. The closer the object is to the background, the closer its colour will be to that of the background (i.e. sky). For example, if looking at a forest of green trees receding into the background which is a blue sky, the colour of the trees will change from the green to the blue of the sky, but will become duller and paler as they near the background.

- The temperature of colours used will change as they recede to match that of the background. Blues are cooler, whereas reds are warmer. If the background is blue and the foreground red, the temperature of the red will slowly change to match that of the background.

- Atmosphere has a significant role to play in the colours we see. The closer something is, the less atmospheric particles there are between the viewer and the object. The further away something is, the more atmospheric particles there are. This atmosphere also impacts the temperature of the colours; those which are closer are much warmer in appearance and those further away much cooler. This also means that when working atmospherically, the further away an object is, the brighter its value and the lighter the colour will be.

- Cast shadows can also play a big part in creating the illusion of depth. Placing the shadow around the outside of the page with n inward gradient, with a person in the middle can create the illusion of a person being in a cave, with their path forwards lit only by the light of a candle. The same is also true for the reverse. If a person is placed on a page with the darkness appearing to radiate from the centre of the page with an outward gradient, the person will then appear to be walking towards a dark hole in the distance.

- The strokes used in the painting process also play a role in creating depth within a piece. Using larger strokes for objects in the foreground and smaller ones for those in the background will assist in creating the illusion of depth. The direction of the brushstrokes will also assist in leading the viewer’s eye inward.

Having discovered these tips and tricks, I am actually rather surprised at just how many things there are to consider when applying paint to a page! I will bear these things in mind when trying to create the illusion of space within my work, whether in interiors pieces or landscape pieces as I believe they could be used to assist in a many number of genres.

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1. Claesz, P. (1630) Vanitas Still Life [oil on panel] At: https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/explore/the-collection/artworks/vanitas-still-life-943/detailgegevens/ (Accessed on April 2020)

Fig. 2. Claesz, P. (1636) A Silver Beaker, a Roemer and a Peeled Lemon [Online] At: https://www.oceansbridge.com/shop/uncategorized/a-silver-beaker-a-roemer-and-a-peeled-lemon (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 3. Claesz, P. (1652) Still Life [Oil Painting] At: https://www.wikiart.org/en/pieter-claesz/still-life-1652/ (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 4. Hals, F. (c. 1623 to 1624) Buffoon Playing a Lute [Oil on canvas] At: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6a/Frans_Hals_-_Luitspelende_nar.jpg (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 5. Hals, F. (1633) Meeting of the officers of the Kloveniersschutterij in Haarlem [Oil on canvas] At: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/40/Frans_Hals_014.jpg (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 6. Hals, F. (c. 1649) Portrait of René Descartes (cleaned up) [Oil on panel] At: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frans_Hals,_Portrait_of_Ren%C3%A9_Descartes.jpg (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 7. Rembrandt (c. 1629) Self-Portrait with Gorget [oil on canvas] At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Rembrandt_van_Rijn_184.jpg (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 8. Rembrandt (1642) The Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburgh, known as the ‘Night Watch’ [oil on canvas] At: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:La_ronda_de_noche,_por_Rembrandt_van_Rijn.jpg (Accessed on April 2020)

Fig. 9. Rembrandt (1669) Self-Portrait [oil on canvas] At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Rembrandt_Harmensz ._van_Rijn_135.jpg (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 10. Boxbarth, J. (c.1700) Library Project [Engraving] At: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Boxbarth_after_Feuillet_Library_interior_c1700.jpg (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 11. Best, M. (1837-1839) Self-Portrait in Painting Room, York [Unknown] At: https://curiator.com/art/mary-ellen-best/self-portrait-in-painting-room-york (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 12. Vemeer, J. (1662 to 1664) The Music Lesson [Oil on canvas] At: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bc/Johannes_Vermeer_-_Lady_at_the_Virginal_with_a_Gentleman%2C_%27The_Music_Lesson%27_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 13. Vemeer, J. (c. 1664) The Concert [Oil on canvas] At: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vermeer_The_concert.JPG (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 14. Vemeer, J. (1670 to 1671) Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid [Oil on canvas] At: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Woman_writing_a_letter,_with_her_maid,_by_Johannes_Vermeer.jpg (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 15. da Milano, G. (1919) Interior of the Painter’s Studio [Oil painting] At: https://www.1stdibs.com/art/paintings/interior-paintings/giulio-da-milano-interior-painters-studio/id-a_6013002/ (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 16. Aafjes, E. (2018) Table Still Life [Oil painting] At: https://www.1stdibs.com/art/paintings/interior-paintings/edwin-aafjes-table-still-life-edwin-aafjes-21st-century-contemporary-oil-painting/id-a_4310672/ (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Fig. 17. Harris, K. (2019) Interior with Piano, Bantry House [Oil on linen panel] At: https://www.1stdibs.com/art/paintings/interior-paintings/kenny-harris-interior-piano-bantry-house/id-a_5607801/ (Accessed on 5 May 2020)

Bibliography

Artnet. (Unknown) ‘Frans Hals (Dutch, 1582-1666)’ [Online] At: http://www.artnet.com/artists/frans-hals-the-elder/ (Accessed on 26 April 2020)

Artnet. (Unknown) ‘Pieter Claesz (Dutch, 1597-1661)’ [Online] At: http://www.artnet.com/artists/pieter-claesz/ (Accessed on 26 April 2020)

Biography. (2014) ‘Rembrandt’ [Online] At: https://www.biography.com/artist/rembrandt (Accessed on 26 April 2020)

Springer Nature. (2017) ‘Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism’ [Online] At: https://www.nature.com/articles/palcomms201768 (Accessed on 26 April 2020)

The Virtual Instructor. (Unknown) ‘The Elements of Art – Space’ [Online] At: https://thevirtualinstructor.com/space.html (Accessed on 1 April 2020)

Visual Arts Cork. (Unknown) ‘Dutch Realist Artists’ [Online] At: http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/history-of-art/dutch-realist-artists.htm (Accessed on 1 April 2020)

Visual Arts Cork. (Unknown) ‘Frans Hals (1582 – 1666)’ [Online] At: http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/old-masters/frans-hals.htm (Accessed on 1 April 2020)

Visual Arts Cork. (Unknown) ‘Harmen van Steenwyck’ [Online] At: http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/old-masters/harmen-van-steenwyck.htm (Accessed on 1 April 2020)

Visual Arts Cork. (Unknown) ‘Pieter Claesz’ [Online] At: http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/old-masters/pieter-claesz.htm (Accessed on 26 April 2020)

Visual Arts Cork. (Unknown) ‘Rembrandt van Rijn’ [Online] At: http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/old-masters/rembrandt.htm (Accessed on 1 April 2020)

Wikipedia. (2020) ‘Composition (Visual Arts)’ [Online] At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Composition_(visual_arts) (Accessed on 1 April 2020)

Wikipedia. (2020) ‘Frans Hals’ [Online] At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frans_Hals (Accessed on 26 April 2020)

Wikipedia. (2020) ‘Interior Portrait’ [Online] At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interior_portrait (Accessed on 26 April 2020)

Wikipedia. (2020) ‘Johannes Vemeer’ [Online] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes_Vermeer (Accessed on 26 April 2020)

Wikipedia. (2020) ‘Pieter Claesz’ [Online] At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pieter_Claesz (Accessed on 26 April 2020)

Wikipedia. (2020) ‘Rembrandt’ [Online] At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rembrandt (Accessed on 26 April 2020)